- Home

- B. H. Fairchild

The Blue Buick Page 11

The Blue Buick Read online

Page 11

a first edition of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

But at the end of the bottom shelf of books that lined

their little trailer was one in French by Blaise Cendrars:

Le Lotissement du ciel (The Subdividing

of the Sky, my translation), the strangest book,

Roy said, he ever read by the most intriguing man

he ever knew. Cendrars, the one-armed legend,

veteran of the front in both world wars, citizen

of a dozen countries, friend of Chagall, Léger,

Apollinaire, Modigliani: a man who had read

everything, done everything, and when Roy

knew him still talked endlessly of Sky’s main subject:

the levitation of saints in the ecstatic state

called by St. John of the Cross al arrobamiento

de amor: the ravishment of love. Cendrars,

the old surrealist, Roy would say, obsessesed

with bodies rising in air when his only son,

the pilot, died by falling to earth. He came back

to this repeatedly. And to Giordano Bruno,

who Roy said was more important than Galileo,

and he taught me Bruno’s memory system,

the nearest thing to immortality, he said,

for then I would forget nothing, and everything

would be imprinted on my soul.

The Journal: Cendrars in “The Ravishment of Love.” “The saint also has his migraines and his gross lassitude. . . . He is suspicious of illusions, dream-somnambulism, the acrobatics of certain drunk and manic states, and the nervous breakdowns of certain epileptics and neurotics.”

So I remembered

everything, the small as well as large, the photo

of Roy and Robert Rossen in Hollywood

(the screenplay of Treasure of the Sierra Madre

with Rossen’s name on it), all the stories

that Maria told of Nijinska and her brother,

the trip to Amarillo when Patsy Cline performed,

even the hometown ball games we would go to,

we three on summer evenings when the fragrance

of new mown outfield grass was hanging in the air

and the lights came on to carve the darkening sky

into a big blue bowl. A ball diamond, he would say,

is the most aesthetically pure form ever given

to a playing field, and as a student of geometry

I could understand that, the way the diamond fits

inside a circle enclosed within a larger one

extending from the arc along the outfield wall.

And the way the game itself falls into curves:

runners rounding base paths; the arc of the long ball’s

sudden rise and floating, slow descent, sometimes

into the outer darkness beyond the left field wall;

the shape a double play can take when the shortstop

snags the ball on his far right and the second baseman

makes a fluid pivot so the ball seems to glide

in an unbroken line around to first; and of course

a killer curve or good knuckle ball by someone like

Preacher Roe or Whitey Ford whose looping arc

briefly mesmerizes the batter it deceives;

all a game of curves and arcs, though Maria

said it was a game of tension, a gathering,

then release, a kind of sexual tension, the way

the pitcher coiled, then unwound, and of course

the explosive letting go, and she said it in a way

that made me stop and think awhile. In a plane once

I saw a diamond far below all lit up,

an emerald resting on the breast of darkness, and now

I recall Maria and the curve from her neck along

the jawline to her raised chin as she followed

the arc of the ball in flight and the way her eyes

gave back the flare of the outfield lights at night.

As with baseball and poetry, so with lathework,

arts of precision: an able catcher sets his feet

to avoid the extra step that makes him miss

the steal at second, a poet hears the syllable

before the word, a good machinist “feels” the cut

before he measures it. These minute distinctions

were Roy’s delight, The Machinist’s Handbook

his guide to prosody. And I tried but somehow

failed the craft—in fact, one time almost ran the bit

into the chuck, unknown to my worried father,

who was losing hope for me: if Roy couldn’t teach me,

who could? But my head was in baseball, books, music:

my tenor saxophone and I would someday be

on 52nd Street in New York, where we belonged,

and so I made Roy talk about his father’s friend,

the great jazz trumpeter, Roy Eldridge, whose name

he took, and the jazz scene in Paris in the fifties

where Roy and Maria on any given night

could hear Bud Powell, Lester Young, Kenny Clarke,

Dexter Gordon, even Sidney Bechet, even sometimes

the Bird himself, and Maria, smiling, recalled

standing outside The Ringside, later The Blue Note,

one night as Parker’s astonishing long riff

on “Green Dolphin Street” rose over the waiting crowd,

over the lamps reflected in the Seine, up and beyond

Haussmann’s Paris and the opulent Palais Garnier,

a black man’s music rising and hovering over

this pearl of Europe from a small room far below

on the rue d’Artois.

Decades later I would walk

this street and others: rue Coquillière,

where Roy met Cendrars, where, I imagined,

he rose finally from the table, feeling the weight,

the burden, of being young and unknown, and strolled

past Saint-Eustache through the jazz-thick air of the clubs

in Les Halles to the little room on rue du Jour

that he shared with Maria, where they drank the last

of their wine and gazed from the balcony toward

the distant future. And whatever they saw there,

it could not have been Liberal, Kansas. What dreams

they must have had! Raising his glass of Chartreuse

after dinner, Roy would sing out the line from Larbaud,

Assez de mots, assez de phrases! ô vie réelle,

and Maria would pull the album from the hope chest

and turn to the photographs, so predictable

they broke your heart: a girl and boy leaning

against the stones of Pont Neuf, the Seine stretching

behind them, the girl small, sharp-boned, bright brown eyes,

a dancer’s bun, and you could almost see her thin lips

trembling with the hesitation that sometimes precedes

pure joy, the boy with slicked-back hair, cigarette

dangling from one hand, the other pressing his girl close.

That evening, I remember, Maria was playing

an old 78 of Bidú Sayão singing Massenet,

and for a moment in my eyes they froze, Maria

lost in thought, staring down into the images

as if she wanted to walk into them, Roy

gazing at his glass as if it were a crystal ball

or piece of lathework, finished, done, no turning back.

We were at a rig just south of Tyrone, Oklahoma,

in No Man’s Land one day inspecting thread damage

on some battered drill pipe when Roy suddenly

turned away and moved into the shadow of our truck,

head down, almost cowering, the dark wing of anguish

sweeping across his face. It’s the light, he said.

> Fucking treeless Oklahoma. Strong light sometimes

brings it on. He reached into the cab and handed me

some rubber tubing. I’ll stay here in the shade.

I’ll be o.k. But if it comes, put this between my teeth

so I don’t bite my tongue. Don’t worry, I’ll know ahead

of time. I’ll warn you. But of course there was no warning

this time as the sun broke behind a cloud and his body

dropped to earth thudding, writhing, shoveling dust

all around as his heels dug in, legs shaking, hands

clawing the ground, and his teeth gnashing so terribly

I could hardly wedge the rubber tube between them.

The St. Christopher was wound around his neck

so tight I had to break its chain, his eyes flaring

and rolling back white as cue balls when the gagging

began its dry sucking sound, that rattle and gasp,

and I knew then that it, the thing, had to be done:

Is there a more intimate gesture than placing one’s hand

in the mouth of another man? All I could think

as I groped inside that mess of flesh and wetness

was how we would be seen from the rig’s deck: two men,

one writhing in the dirt, the other strangling him

in the last throes of dying, and when it was over

and he lay there breathing fast and staring at the sky,

I thought that I had died, not him, and I rose up

and watched with dead eyes two dust devils in the distance

spinning out across the barren fields of No Man’s Land.

The Journal: Told Maria today. Says it’s just too dangerous. But what the hell else can I do? Terrible, terrible sight for a young kid. This time on a bridge with Maria, the river is black, sky black, a photographic negative. That bizarre music again, like The Isle of the Dead. The rising into light, probably only a second, but so slow, Nijinsky, now there was a man with a fire in his head. And kingdoms naked in the trembling heart—Te Deum laudamus O Thou Hand of Fire.

I know how Roy and I must look to you, she said.

We seem like . . . , she tried, you must think . . .

Roy passed out on phenobartibal, radio off,

we were driving back from Wichita where our team

had won a tournament that day. Grain elevator,

church spire in the distance, one more small town,

and twenty miles after that, another. A patch

of soybean flung forward by the sweep of headlights,

long shadow of a stand of maize, then nothing

but the night sky slipping like a sequined and slowly

unwinding bolt of black cloth across the Buick’s hood,

the earth rolling beneath the rolling car so that,

a child might think, they would return in time and space

to the same point, same field of bending wheat,

DEKALB sign rattling on a fence post, wind sifting

through high grass, moaning on barbed wire—my life, I thought.

I knew what she was trying hard to say, and not

to say: failure. That’s how Roy and I must seem to you.

No, I said, not at all. But she wouldn’t hear of it,

and so began the litany of failure in America,

wind pushing the tears sideways across her face,

Bright beginnings, yes, I guess, but no grief here,

none. By God, we’ve made a life, and that’s enough:

a life. Listen, Nijinsky went nuts. Bronislava,

a driven woman. All those big-shot émigrés

in Santa Monica trying to believe they were on

vacation in the south of France. What brought us here,

I don’t understand. One thing happens. Then another.

We make do. We survive. It’s just not that complex.

Oh yes it was. I was seventeen, and I knew.

It was vast, entangled, difficult, profound.

And as we rolled on through the deep sleep of small towns

strewn along the highway, the odd light of a house

like a single unshut eye somewhere on the edge,

the silence of the high plains huge yet imminent,

like the earth’s held breath, I knew, it was not here

That’s what I mean, stud, Roy would say, that’s my point

exactly. The held breath. As if we haven’t quite

begun yet to exist. That coming into being

still going on. That final form just waiting,

the world waiting. And it’s not just geography,

though that’s part of it. Anderson had a sense of this

in Winesburg, those tragic little lives bordering

on something unknown, possible, huge—Dickinson,

too, sitting in her little room, Jesus, the walls

must have vibrated. For God’s sake, this is not

the Wasteland, kid. London is. Or Paris.

This place has no history. And if you want to see

the absolute end of the road, try Venice.

You’ll fall in love with her, everybody does,

but on the honeymoon you’ll find you’re crawling

in bed with a corpse. There are people still living

in this town who came up on the Jones and Plummer trail

when the only law was that the strong survived

and the weak didn’t, who knew and lived something that

Kropotkin only dreamed: a state of total anarchy.

You know, L.A. was once like this. And then Chandler

and his pals moved in and conspired to do

what Lorenzo de’ Medici had planned for Florence

and the Arno: divert a river so that one town

died and another prospered. So L.A. grew

and became what? A false Florence with faux-European

architecture, fake art (read Nathanael West),

synthetic landscape, and right next door on the coast,

a phony Venice with canals and everything.

And Chandler became the new, improved Medici,

all spiritual possibility gone, bought and sold,

infinities of human imagination

subdivided and air-conditioned. And, of course,

the new politics: metaphysical democracy—

nothing is genuine, everything is equally unreal.

Well, I’d rather be here.

And he pulled a book

from the shelf and read again in a too-loud,

prophetic voice those strange lines from Crane’s The Bridge:

And kingdoms

naked in the

trembling heart—

Te Deum laudamus

O Thou Hand of Fire

So I’ve forgotten nothing, but if I had,

I would still remember this: one evening after

working late to finish out a load of drill pipe

when Maria drove up as usual to take us home

but made us wait in the car with the headlights on.

So we waited, high beams bright as stage lights against

the big front door in the midnight dark. We heard

the electric lift begin to hum as the door rose

slowly to reveal, inside, Maria in her white slip.

No music. Just wind pushing bunchgrass against

a stack of cold roll and the rattle of a strip

of tin siding somewhere. And she began to dance.

Against a backdrop of iron and steel, looming hulks

of lathes and drill presses, tools scattered in the grease

and dirt, this still lithe, slim, small-boned creature

began to move silently, just the dry, eggshell

shuffle of her feet against the floor, began to glide,

leaping, spinning, rising, settling like a paper

tossed and floating in a breeze. I saw her then the way

the first time. And I remember thinking, so this

is how it was, had been, for her on stage in Paris

or California when there was a future in her life.

The idling engine made the headlights shudder

so her body shimmered in a kind of silver foam,

and then turning quickly in a sweeping motion

into the center of the light, she stopped, froze,

head lifted in profile, wide-eyed, looking astonished

and a little fearful, a face that I had seen before,

and late that night I found it in my Gombrich’s:

the orphan girl, by Delacroix. And I can tell you

that since that evening it’s the face I’ve looked for

in every woman that I’ve known.

The Journal: The holy disease without the holiness. Worse, without the words. Ex-poet. The X poet. I swallowed my tongue years ago. Bad joke. But I still pray—a bird, rising. Cendrars: “Mental prayer is the aviary of God.”

It all came apart

in L.A., she said, studying me through a wineglass

after Roy had gone to bed. Roy fell in

somehow with Robert Rossen, the master craftsman

of screenplays, first writer on Sierra Madre

before Huston took it over. But Rossen was

an ex-Red who at first refused to testify and then

used fronts and pseudonyms, the way they all did

those awful years the blacklist was in force.

They had collaborated on a script about

the Owens River deal: buying up the land

of unsuspecting farmers, posing as agents

of the reclamation project, then rigging up

a bond issue that would bring the water

not to L.A., as advertised, but to land purchased

by the city fathers downtown who thereby

made a ton, believe me. Biggest land scam

in this country’s history since Manhattan island.

And no one complained because they all got fat

somewhere down the line as the water poured in

and land values soared. As Roy always said,

it’s history’s greatest lesson: if enough people

commit a crime, it’s not a crime anymore.

And because Roy was not a Red, they put his name

on the manuscript. What a stupid thing to do.

Of course, the script found its way downtown, some strings

were pulled, pressure brought to bear, and suddenly

Roy had no career, especially since through the tie

with Rossen he was suspect anyway. Her voice

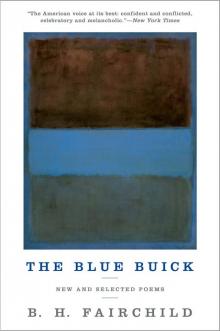

The Blue Buick

The Blue Buick