- Home

- B. H. Fairchild

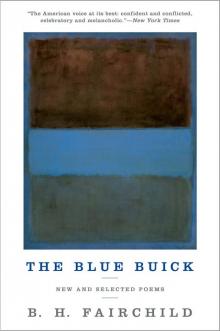

The Blue Buick

The Blue Buick Read online

The Blue Buick

NEW AND SELECTED POEMS

B. H. FAIRCHILD

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

INDEPENDENT PUBLISHERS SINCE 1923

NEW YORK | LONDON

Adjusting type size may change line breaks. Landscape mode may help to preserve line breaks.

FOR PATRICIA LEA FAIRCHILD,

the air that I breathe

Perhaps they found this front-line trench

at break of day as fully charged as any chorus-end

with hopes and fears; . . . Certainly they sat

curbed, trussed-up, immobile, as men who

consider the Nature of Being.

—DAVID JONES, In Parenthesis

CONTENTS

FROM

The Arrival of the Future

(1985)

The Woman at the Laundromat Crying “Mercy”

The Men

The Robinson Hotel (from Kansas Avenue)

Flight

Angels

Groceries

Night Shift

Hair

To My Friend

The Limits of My Language: English 85B

Late Game

FROM

Local Knowledge

(1991)

In Czechoslovakia

In a Café near Tuba City, Arizona, Beating My Head against a Cigarette Machine

Language, Nonsense, Desire

There Is Constant Movement in My Head

Maize

In Another Life I Encounter My Father

The Machinist, Teaching His Daughter to Play the Piano

The Doppler Effect

Toban’s Precision Machine Shop

Speaking the Names

Local Knowledge

Kansas

The Soliloquy of the Appliance Repairman

Work

L’Attente

FROM

The Art of the Lathe

(1998)

Beauty

The Invisible Man

All the People in Hopper’s Paintings

The Book of Hours

Cigarettes

The Himalayas

Body and Soul

Airlifting Horses

Old Men Playing Basketball

Old Women

Song

Thermoregulation in Winter Moths

Keats

The Ascension of Ira Campbell

The Dumka

A Model of Downtown Los Angeles, 1940

The Children

Little Boy

The Welder, Visited by the Angel of Mercy

The Death of a Small Town

The Art of the Lathe

FROM

Early Occult Memory Systems

of the Lower Midwest

(2003)

Early Occult Memory Systems of the Lower Midwest

Moses Yellowhorse Is Throwing Water Balloons from the Hotel Roosevelt

Mrs. Hill

The Potato Eaters

Hearing Parker the First Time

Delivering Eggs to the Girls’ Dorm

Rave On

A Photograph of the Titanic

Blood Rain

The Death of a Psychic

Luck

A Roman Grave

On the Passing of Jesus Freaks from the College Classroom

Brazil

Weather Report

The Second Annual Wizard of Oz Reunion in Liberal, Kansas

The Blue Buick

Mlle Pym (from Three Poems by Roy Eldridge Garcia)

The Deposition

A Starlit Night

Motion Sickness

A Wall Map of Paris

At the Café de Flore

At Omaha Beach

The Memory Palace

FROM

Usher

(2009)

The Gray Man

Trilogy

Frieda Pushnik

Usher

Hart Crane in Havana

Key to “Hart Crane in Havana”

The Cottonwood Lounge

Les Passages

Wittgenstein, Dying

The Barber

Hume

Gödel

from The Beauty of Abandoned Towns

1. The Beauty of Abandoned Towns

2. Bloom School

3. The Teller

4. Wheat

Madonna and Child, Perryton, Texas, 1967

What He Said

from Five Prose Poems from the Journals of Roy Eldridge Garcia

Cendrars

Piano

Moth

Triptych: Nathan Gold, Maria, On the Waterfront

Nathan Gold

Maria

On the Waterfront

New Poems

The Story

Red Snow

The Left Fielder’s Sestina

Betty

The Game

The Student Assistant

History: Four Poems

1. Dust Storm, No Man’s Land, 1952

2. Shakespeare in the Park, 9/11/2011

3. Economics

4. Alzheimer’s

Three Girls Tossing Rings

The Death of a Gerbil

Pale from the Hand of the Child That Holds It

Three Prose Poems from the Journals of Roy Eldridge Garcia

An Attaché Case

The End of Art

The Language of the Future

Language

Abandoned Grain Elevator

The Men on Figueroa Street, Los Angeles, 1975

Getting Fired

On the Death of Small Towns: A Found Poem

Leaving

Swan Lake

Obed Theodore Swearingen, 1883–1967

Rothko

A House

Poem (from Early Occult Memory Systems of the Lower Midwest)

Poem

Notes

Acknowledgments

FROM

The Arrival of the Future

(1985)

The Woman at the Laundromat

Crying “Mercy”

And the glass eyes of dryers whirl

on either side, the roar just loud enough

to still the talk of women. Nothing

is said easily here. Below the screams

of two kids skateboarding in the aisles

thuds and rumbles smother everything,

even the woman crying mercy, mercy.

Torn slips of paper on a board swear

Jesus is the Lord, nude photo sessions

can help girls who want to learn, the price

for Sunshine Day School is affordable,

astrology can change your life, any

life. Long white rows of washers lead

straight as highways to a change machine

that turns dollars into dimes to keep

the dryers running. When they stop,

the women lift the dry things out and hold

the sheets between them, pressing corners

warm as babies to their breasts. In back,

the change machine has jammed and a woman

beats it with her fists, crying mercy, mercy.

The Men

As a kid sitting in a yellow-vinyl

booth in the back of Earl’s Tavern,

you watch the late-afternoon drunks

coming and going, sunlight breaking

through the smoky dark as the door

opens and closes, and it’s the future

flashing ahead like the taillights

of a semi as you drop over a rise

in the road on your way to Amarillo,

bright lights and blonde-haired women,

as Billy used to say, slumped

over

his beer like a snail, make a real man

out of you, the smile bleak as the gaps

between his teeth, stay loose, son,

don’t die before you’re dead. Always

the warnings from men you worked with

before they broke, blue fingernails,

eyes red as fate. A different life

for me, you think, and outside later,

feeling young and strong enough to raise

the sun back up, you stare down Highway 54,

pushing everything—stars, sky, moon,

all but a thin line at the edge

of the world—behind you. Your headlights

sweep across the tavern window,

ripping the dark from the small, humped

shapes of men inside who turn and look,

like small animals caught in the glare

of your lights on the road to Amarillo.

The Robinson Hotel

from Kansas Avenue, a sequence of five poems

The windows form a sun in white squares.

Across the street

the Blue Bird Cafe leans into shadow and the cook

stands in the doorway.

Men from harvest crews step from the Robinson

in clean white shirts

and new jeans. They stroll beneath the awning,

smoking Camels,

considering the blue tattoos beneath their sleeves,

Friday nights

in San Diego years ago, a woman, pink neon lights

rippling in rainwater.

Tonight, chicken-fried steak and coffee alone

at the Bluebird,

a double feature at The Plaza: The Country Girl,

The Bridges at Toko-Ri.

The town’s night-soul, a marquee flashing orange

bulbs, stuns the windows

of the Robinson. The men will leave as heroes,

undiscovered.

Their deaths will be significant and beautiful

as bright aircraft,

sun glancing on silver wings, twisting, settling

into green seas.

In their room at night, they see Grace Kelly

bending at their bedsides.

They move their hands slowly over their chests

and raise their knees

against the sheets. The Plaza’s orange light

fills the curtains.

Cardboard suitcases lie open, white shirts folded

like pressed flowers.

Flight

In the early stages of epilepsy there occurs a characteristic dream. . . . One is somehow lifted free of one’s own body; looking back one sees oneself and feels a sudden, maddening fear; another presence is entering one’s own person, and there is no avenue of return.

—GEORGE STEINER

Outside my window the wasps

are making their slow circle,

dizzy flights of forage and return,

hovering among azaleas

that bob in a sluggish breeze

this humid, sun-torn morning.

Yesterday my wife held me here

as I thrashed and moaned, her hand

in my foaming mouth, and my son

saw what he was warned he might.

Last night dreams stormed my brain

in thick swirls of shame and fear.

Behind a white garage a locked shed

full of wide-eyed dolls burned,

yellow smoke boiling up in huge clumps

as I watched, feet nailed to the ground.

In dining cars white tablecloths

unfolded wings and flew like gulls.

An old German in a green Homburg

sang lieder, Mein Herz ist müde.

In a garden in Pasadena my father

posed in Navy whites while overhead

silver dirigibles moved like great whales.

And in the narrowing tunnel

of the dream’s end I flew down

onto the iron red road

of my grandfather’s farm.

There was a white rail fence.

In the green meadow beyond,

a small boy walked toward me.

His smile was the moon’s rim.

Across his eggshell eyes

ran scenes from my future life,

and he embraced me like a son

or father or my lost brother.

Angels

Elliot Ray Neiderland, home from college

one winter, hauling a load of Herefords

from Hogtown to Guymon with a pint of

Ezra Brooks and a copy of Rilke’s Duineser

Elegien on the seat beside him, saw the ass-end

of his semi gliding around in the side mirror

as he hit ice and knew he would never live

to see graduation or the castle at Duino.

In the hospital, head wrapped like a gift

(the nurses had stuck a bow on top), he said

four flaming angels crouched on the hood, wings

spread so wide he couldn’t see, and then

the world collapsed. We smiled and passed a flask

around. Little Bill and I sang “Your Cheatin’

Heart” and laughed, and then a sudden quiet

put a hard edge on the morning and we left.

Siehe, ich lebe, Look, I’m alive, he said,

leaping down the hospital steps. The nurses

waved, white dresses puffed out like pigeons

in the morning breeze. We roared off in my Dodge,

Behold, I come like a thief! he shouted to the town

and gave his life to poetry. He lives, now,

in the south of France. His poems arrive

by mail, and we read them and do not understand.

Groceries

A woman waits in line and reads

from a book of poems to kill time.

When her items come up to be counted,

the check-out girl greets the book

like a lost child: The House on Marshland!

she says, and they share certain lines:

“the late apples, red and gold, / like words

of another language.”

The black belt rolls on. Groceries flow,

coagulate, then begin to spill over: canned

corn, chicken pot pies, oatmeal, garden

gloves, apricots, sliced ham, frozen pizza,

loaves and loaves of bread, and then the eggs,

“the sun is shining, everywhere you turn is luck,”

they sing. Here comes the manager, breathless,

eyes like tangerines, hair in flames.

Night Shift

On the down side

of the night shift:

the wind’s tense sigh,

the heavy swivel

turning, turning.

Pulling out of the hole

from four thousand feet

straight down,

we change bits, the moon

catching in the old one

a yellow gleam wedged

in mud, a shark’s tooth.

The drawworks rumbles

like a flood rushing over

flat stubble fields

that stretch for miles,

all surface, no depth

until now, swept under

ocean, the moon wavering

behind clouds

like a floating body

seen from underwater.

I see small eyes,

feel the hard gray skin

slipping past, and think

of origins, the distances

of time, the absence

of this rig, these men.

On the long drive home

I’ll head into a sun

that stared the sea away,

that saw a dried tooth

sink into the darkness

I return to.

Hair

At the

23rd Street Barber Shop

hair is falling across the arms of men,

across white cotton cloths

that drape their bodies like little nightgowns.

How like well-behaved children they seem—

silent, sleepy—sheets tucked

neatly beneath their chins,

legs too short to touch the floor.

Each in his secret life sinks

easily into the fat plastic cushion

and feels the strange lightness of falling hair,

the child’s comfort of soft hands

caressing his brow and temples.

Each sighs inwardly to the constant

whisper of scissors about his head,

the razor humming small hymns along his neck.

They’ve been here a hundred times,

gazed upon mirrors within mirrors,

clusters of slim-necked bottles labeled WILDROOT

and VITALIS, and below the shoeshine stand,

rows of flat gold cans. They’ve heard

the sudden intimacies, the warmth

of men seduced by grooming: the veteran

confessing an abandoned child in Rome,

men discussing palm-sized pistols,

small enough to snuggle against your stomach.

As children they were told, after you’re dead

it keeps on growing, and they’ve seen themselves

lying in hair long as a young girl’s.

Two of them rise and walk slowly out.

Their round heads blaze in the doorway.

They creep into what is left of day, fingertips

touching the short, stiff hairs across their necks.

To My Friend

To my friend they all look like movie stars.

“Here comes Herbert Lom,” he’ll say, and a guy

in a low-angle shot looms over us, bulging

forehead shouting treason to pedestrians.

This history of personalities repeats itself each day.

“Take a look at ZaSu Pitts behind the pineapples”

or “Jesus, Zachary Scott sacking groceries!”

He collects them like old stills, hunts for them

in every bar, smoke-curls and clicking glasses

whispering sly promises of Sidney Greenstreet.

Or at traffic lights: Ginger Rogers in a Dodge,

Errol Flynn on a blue Suzuki. The glamour

of appearances. The way montage erases vast

ontological gaps. A wino as Quasimodo as Anthony

Quinn explains the brunette cheerleader, who is

really Gina Lollobrigida. Life connects this way,

but huge sympathies are lost in a single shot.

The Blue Buick

The Blue Buick